What a Desexy Movement Could Be

We have reached the wrapping up point of desexy. It’s been a wild few weeks of research, interviews, and writing to get here. While I’ve only begun to scratch the surface of discussions of desexualization, I wanted to thank those who have been reading for your support. This project couldn’t have happened without you.

In this final post, I want to leave you with some of the insights I’ve gained after writing for desexy on what a movement that celebrates “out-of-the-box” sexuality could look like.

- We have more in common than we think.

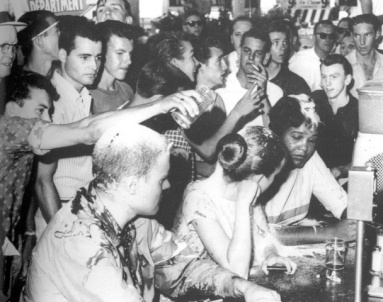

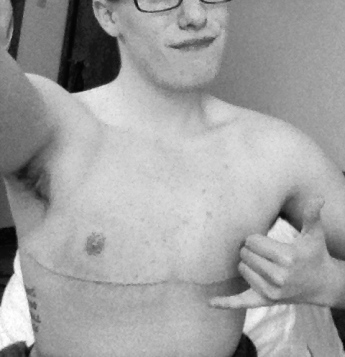

Cross-movement work serves as the foundation for social justice movements. The early homophile, sexual liberation, and gay rights movements not only supported the Civil Rights Movement but also borrowed tactical frameworks. For example, the CRM popularized the sit-in, borrowed by ACT UP in the early 1980s and most recently seen in the Black Lives Matter movement in response to police brutality against Black Americans (seen in the pictures below). This shared commonality not only exists in the ways social justice movements advocate for change. Marginalized communities often share similar struggles in terms of access and experiences. For example, trans justice and disability justice movements fight for safe and accessible physical spaces (like bathrooms, locker rooms, and housing). As I mentioned in my first post, Alex+ and I found that we both experienced desexualization because we had “non-normative” bodies. Understanding that people who hold different identities may also experience desexualization can allow for the facilitation of discussion.

Source: Mashable

- We can create communities and social spaces where we can support one another in an affirming way.

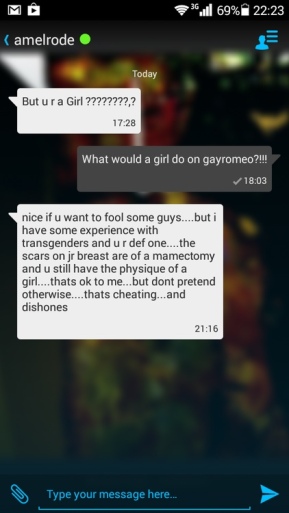

Sharing our experiences of intimacy is already a difficult task. Adding layers of rejection based on oppressive structures makes it all the harder. People who work in social justice or live at the intersections of marginalized identities can often have a difficult time unlearning oppressive behaviors themselves.

“What we do need is discussion and acknowledgment, not as a defiance of our desires, but to perhaps understand how external forces narrow their scope. Acknowledging the prioritizing of certain bodies and identities is just the beginning, and will lead to many difficult conversations…but ultimately can only lead to more understanding, more inclusiveness, and stronger communities.” (“Dating from the Margins: Desexualizing and Cultural Abuse”)

We need to create spaces that allow us to call out people with care (rather, calling people in) to hold ourselves accountable for our actions and learned prejudices in regards to attraction, intimacy, and sexuality.

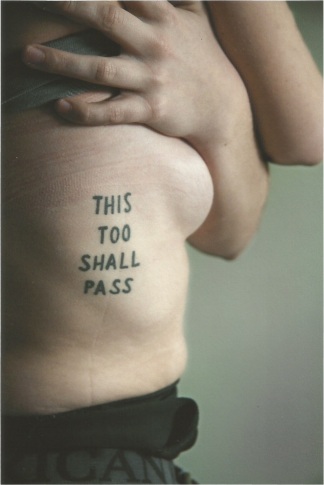

- Reclaim, redefine, own, empower, deconstruct, reconstruct.

The spaces we build can allow us as individuals or collectively as communities to name ourselves. We can celebrate the pain, awkwardness, and rejection inherent to desexualization by leaning into that discomfort and defining sexuality on our own terms. As people who experience this form of interpersonal oppression, we can innovate ways to empower ourselves sexually in opposition to these oppressive attitudes. We can listen to disabled people in our communities talk about the rich and complex diversity of disabled sexuality, and how they overcome physical obstacles through “invention, creativity, cleaver adaptation, and brilliant accommodation” when it comes to sex” (“Desexualizing Disability”). We can be like founders of the Rose Centre for Love Sex and Disability, Tim and Natalie, and find ways to show affection for our partners in nontraditional ways:

“I used to think I was bad at sex because I can’t do it in the traditional way,” says Tim. “So I didn’t enjoy it. And I thought it was wrong that I didn’t enjoy it. It wasn’t until I had a partner, Natalie, who was willing to say, ‘OK, let’s figure out what works for the two of us’ that it started to be great.” (Dean)

We don’t have to work around our body differences; we can work with them. We can completely redefine what sex and sexuality mean to us, even if that means not experiencing sexual or romantic attraction at all. We can boldly claim that our identities are the sexiest parts of us, because would we really be us without them?

Being desexy is more than just lamenting painful experiences of rejection; it’s what you do to redefine (and relearn) your sexuality because of them.

References

“Dating from the Margins: Desexualizing and Cultural Abuse.” Gudbuy T’Jane. WordPress, 13 Oct. 2011. Web. 2 Jan. 2015.

Dean, Jamieson. “Surprise! Disabled people have sex.” The Star. Toronto Star Newspapers Ltd., 5 Oct. 2014. Web. 1 Jan. 2015.

Smith, S.E. “Desexualising Disability.” This Ain’t Livin’. S.E. Smith, 2014. Web. 2 Jan. 2015.